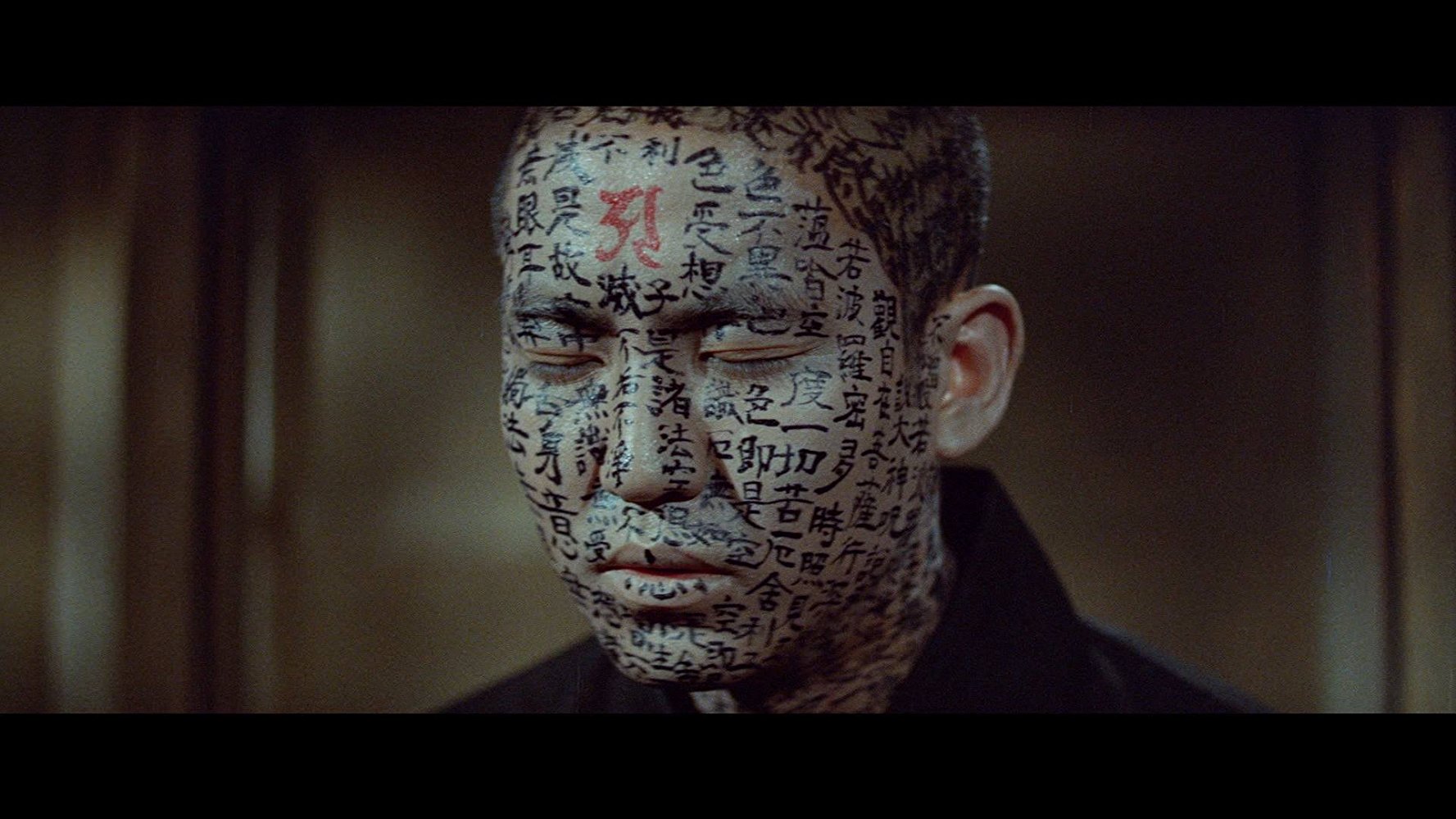

Katsuo Nakamura in Kwaidan (1964)

Hōichi was a young man who was particularly adept at playing the biwa, a Japanese stringed instrument. His excellence in playing the biwa especially extended to his performance of the Tale of the Heike, for which he was known to make audiences weep. Hōichi, however, was blind and a pauper that lived in an isolated temple. As it were, word spread of his ability to strum and sing the Tale of the Heike. In time, a samurai began to call on Hōichi to play for a group while the priest of the temple was out at night. Hōichi, unable to refuse, would play to the hours of dawn. Little could be done to refuse the request of a samurai, for Hōichi had little status. The priest, suspicious of Hōichi after learning of his late night rendezvous, thought he should find out where the young boy was going every night. He sent other young boys to find Hōichi’s destination.

The Tale of the Heike is an epic account of the Gempei War between the Taira and Minamoto clans of medieval Japan. In the final struggle, the last of the Taira clan—women, children, and all—jumped into the ocean to death rather than face defeat from their opponents. The young boys found the blind Hōichi performing for floating flames—the spirits of the dead Taira clan, who were especially moved by his performance of the scene in which they all perished in the sea.To protect Hōichi from playing for the dead again, the priest would later write prayers across his body.

Richard Lloyd Parry’s Ghosts of the Tsunami: Death and Life in Japan’s Disaster Zone is a rendering of the earthquake and subsequent tsunami of March 11th, 2011, on the Sanriku Coast of Japan’s Tōhoku region. Rather than engross himself in the totality of the disaster, he slices up specific aspects of the disaster. His focus centers upon the tsunami, not the earthquake or the resulting failure of the nuclear plant; he hones in on a specific event on the Sanriku coast as both exemplary and unique to the magnitude of calamity and harrowing sorrow of the disaster; and, he allows the voices of the survivors to be heard in their brutal grief. Parry approaches the subject with clarity despite his long-time residence in Japan and his own fear of being emotionally compromised by the situation’s gravity. Ghosts of the Tsunami is a book about what remains the same in the face of appallingly visible change to the landscape. It is also a microcosm of Japanese idiosyncrasy and a voucher for the extraordinary effects that the tsunami had on the survivors’ psyche and comprehension of reality.

According to the National Police Agency of Japan, 18,434 people are dead or missing because of the March 11th earthquake and subsequent tsunami. 99% of those that died were killed in the water, described as “a thing of a different order, darker, stranger, massively more powerful and violent,” and as black, white, and brown—but never sea blue. The Fire and Disaster Management agency records 22,062 dead or missing and includes those who died after the tsunami from causes including suicide. The quake shook the earth 4 inches off its axis and moved the archipelago several feet. Thousands of people have still not returned home. The wave removed whole communities from the earth; it swept up boats and deposited them in city centers; rivers overflowed miles inland from the coastline.

Tōhoku, the northeastern region of the main island, Honshū, was most affected by the tsunami. The region makes up one-third of the total area of Honshū, but carries only one-tenth of its population. Parry explains that the Tōhoku region “[i]n ancient times…was a notorious frontier realm of barbarians, goblins, and bitter cold.” Today, it remains distinct from the more outwardly modern Japan as a “remote, marginal, faintly melancholy place, the symbol of rural tradition that, for city dwellers, is no more than a folk memory.” (53-54) For many Japanese, the Tōhoku region remains a place to be imagined rather than experienced.

Parry magnifies his focus until he arrives at the individual level, just as a series of maps indicate on the book’s opening pages. The linchpin of the book is the destruction of Okawa Elementary School in Kamaya, where 84 perished, including 74 children. The failure of teachers and administrators to properly respond to the danger of the tsunami and the questions of parents afterwards is revealed through accounts of school board meetings and Parry’s interviews with the parents of lost children. Junji Endo, the only surviving teacher of the school is a pillar of pity and curiosity throughout. The questions about his survival over 74 children intensify as more detail trickles out. As Parry interviews parents and produces accounts of their attempt at reconciliation, he understands that they divide themselves along lines of loss. Divisions appeared between those who had lost their whole family and those who had lost only their parents or children. Whether loved one’s remained lost—swept to sea, buried in the muck—was another divide. The parents of Okawa Elementary School even separated based on how they interacted with the school administrators’ pitiful responses. Despite their discord, the survivor’s voices are clear and powerful throughout, some searching for reconciliation at least five years later.

Japan in the post-World War Two era is often defined, in part, by the atomic bombings. Ghosts of the Tsunami may briefly fall into the trap of referencing the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a main comparative reference for the earthquake and tsunami—not the Fukushima power plant disaster. Parry points out in the epigraph to the prologue that this was the single greatest loss of life since the bombing of Nagasaki—and this is a relevant point. Parry can hardly be described as putting words into the mouths of Japanese anyways, because following the disaster there were mass protests of nuclear power associated with atomic weaponry. Hitomi Konno described the obliteration of Kamaya thus, “everything had disappeared. It was as if an atomic bomb had fallen.” An elderly protester who had lived through the Second World War, felt that history was walking backwards—his cousin had died in the bombing of Hiroshima. And although the Japanese psyche appears shaped by the atomic bombings and their legacy, certain references are unnecessary. “The tsunami had the power of many atomic bombs,” again frames the natural disaster in terms of manmade destruction. In discussing Tokyo preparations and death estimates for an earthquake and tsunami, he describes the death counts in fractions of loss at Nagasaki and Hiroshima. To reframe the death tolls this way, seems to pull away from his intended purpose of isolating Tōhoku and the tsunami. The need to reference mass casualty in Japan in terms of atomic weaponry is a negation of the progress that Japan has achieved since that terminus.

Parry’s work absolutely fascinates in its exploration of the way that the tsunami and death impacted spiritual life in Tōhoku. In the “cult of the ancestors,” the living are responsible for ferrying their ancestors into the afterlife through proper burial and appropriately caring for their spirits at the household butsudan—a household altar to the gods. The tsunami dislodged many stewards of the ancestors and sent many more into the afterlife without a prompt and traditional funeral. So, those spirits wandered their land, awaiting proper rites, awaiting a body to bother.

Reverend Kaneta Taio, the chief priest of a Zen Temple in Kurihara, performed 200 rituals for the dead in a single month after the disaster. Kaneta also counseled survivors who saw ghosts. The idea that a person would see ghosts, especially following a tragedy of that magnitude was wholly coherent in Tōhoku. Men and women skulking with muddy clothes and taking taxis rides to non-existent structures were looked after in reverence. A dead neighbor appeared in the living room of a refugee community—“the cushion on which she had sat was wet with seawater.” Many had been sent to a purgatorial realm, and whether ghosts were normal or not was not the question—it was how to respectfully usher them into the afterlife.

Kaneta also counseled against more sinister encounters with the dead. “A young man complained of pressure on his chest at night…a teenage girl spoke of a fearful figure who squatted in her house. A middle-aged man hated to go out in the rain, because of the eyes of the dead, which stared out at him from puddles.” One man became possessed with no recollection of snarling at his wife and mother-in-law, “you must die. You must die.” The man writhed and roared throughout the night. Kaneta performed dozens of exorcisms on one young woman—a man who died in the Second World War and many many survivors lost in the tsunami, all undone by water, possessed her body. This woman, who became a vessel, would speak deep into the night. Eventually, she relented to the possessions, willingly becoming part of the process for ferrying the dead to the afterlife. The accounts of ghost sightings and possessions are purely captivating and the most readable sections of Ghosts of the Tsunami.

These sorts of experiences all mesh with a rich tradition of ghost stories in Japan. The dead inhabit many of the same spaces that the living do, and they blur the lines between the dead and the living. The story of Hōichi, the blind biwa player may appear a simple folk relic, but perhaps it is realer than we might realize. Lafcadio Hearn, the Greek transplant to Japan who earned a Japanese name in the 19th century, translated that story and others in his ruminations on Japan titled, In Ghostly Japan.

Still, further beyond Japan, we are reminded how much power that death and the dead hold over us. Drew Gilpin Faust’s, This Republic of Suffering, charted the importance of the “good death” in her work on the American Civil War. The scramble to appropriately bury the dead was so bitterly disrupted by the attrition of that war in the same way that the proper burial of, and worship of the dead was disrupted in Japan. The Japanese survivor’s anguished over a “good death,” quickly seeking to perform funeral rites with priests like Kaneta. More broadly, Thomas Laqueuer’s The Work of the Dead, although examining British understanding of death for hundreds of years, highlights how much power the dead hold over us. We labor for the dead, in Britain and Japan, to secure a safe ferry into the afterlife by creating mausoleums, by lighting incense, by exorcising tormented spirits. There appears to be some similarity in how different cultures treat the dead, and how they labor in their service.

As the work closes out, Ghosts of the Tsunami ultimately is a work about the things that have changed and that remain the same. Tōhoku stands further askance from the rest of Japan. Signs across the archipelago declared, “Ganbarō Tōhoku,” or “do your best.” Parry points out that the phrase, when applied to utter destruction is not congruent with the gravity of the situation, and has linguistic-cultural connotations akin to gritting one’s teeth for an ultimately positive outcome. Japan appears to have distanced itself from the northeastern region. But so many lives were irreparably changed that day, and the absence of the dead and living from those communities cannot simply be replaced through the burning of incense. Many disembodied dead may roam the coastline, searching for their own folklore tale to weep to—and Parry may have provided something like a replacement to sooth those tormented spirits.